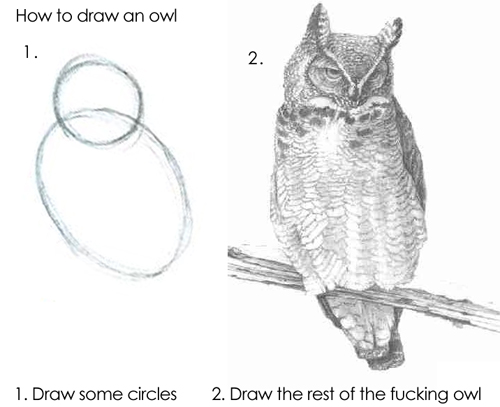

The Rest of the Owl

Sometimes you have to break problems down into two simple steps.

Many years ago I found myself, with no managerial experience, having to manage a staff member. I’m not going to write anything about who he was or the company I worked at at the time, other than that he was the junior developer in my team.

He was stuck on a task: building a bespoke, dynamic data sheet for a fussy customer, one of many in a long line of what had been frustrating busywork for some demanding clients. The data sheet was complex, and understanding it relied on knowing a lot of technical jargon and systems in our client’s industry (and moreso, their particular flavour of it).

The problem for the young developer is that he couldn’t see past the finished product, which didn’t exist yet, and was growing disillusioned with his coding abilities: other devs were able to produce these pages with ease, he was struggling to even comprehend what he was meant to do. But it only looked this way from his perspective: it looked like we were kind of making our work appear out of whole cloth, because he only saw the finished products when we submitted the work; he couldn’t appreciate that we were struggling with the same frustrating task of creating these things from scratch.

He wanted to know my process, so we sat down, and tried to break his data sheet apart into steps.

I asked, if we boil this right down, what is this sheet?

He replied that you can’t boil it down easily, what they want is too complex.

Well, I said, let’s just be dumb. What this sheet is really, is a just a web page. So start there. Make a blank page, and make it load. Add in the route so you can open it in the app. Simple.

Next, the presentation may be complex, but we easily know what set of data we need. So grab that. Just dump the raw data on the page. Who cares? Nobody is going to see this yet, so you’re just dumping all your toys out in front of you to see what you’ve got.

Next, we know they need to see these data sorted into days of the week. Ok, make a table with seven days and dump the pieces of the raw data accordingly.

And so on…

Allow yourself to get out of your headspace, and just think what’s the next smallest step? Don’t worry about the finished product until you get there. Just keep iterating bit by bit and you’ll see it come together.

That’s just two things

I’m currently working on a big project: modernising the fundamental core of our application — the module responsible for loading and handling the data at the heart of our business. (The actual details are proprietary, and I’m struggling to balance being specific enough without actually describing anything…)

The original was written almost 15 years ago, and it’s structure was perfectly fine for what it was. It had a fairly standard method for a web app written in a PHP MVC framework, of loading data from a MySQL database, processing it, and rendering it to the page. But since then our clients have grown, both in number and in size. What was once fine, is now slow; and as more and more features have been added, and more, larger clients create more data, it’s starting to get bloated.

We’re a bit unusual. In a typical web app, at any given time, you’re picking up a small amount of data, doing a quick transformation, and rendering something to the page. Larger processes tend to be infrequent; you don’t often pick up very large datasets, crunch them, and try to render them to the browser. That tends to be relegated to more infrequent things, like monthly reports, or things that can be run in background tasks or batch processed. If you have to read data frequently, you would try to cache it. The core model of our business, however, requires us to load potentially huge datasets and present them all at once: our clients need to do this all the time, it’s their most frequent use case. And the most read data, is also the least cacheable — they keep changing it.

You might think, well, a PHP webapp was clearly a mistake, you should use something more fundamentally performant. But we don’t have the luxury of that. We started in PHP, it was all perfectly fine in PHP (until it wasn’t), and we’ve spent well over a decade building a PHP application: porting it to another language or system while maintaining our existing clients and business would require many times the human-hours than we could possibly muster. Imagine trying to replace the engine in your car, while you’re driving down the motorway. Besides, an inefficient algorithm doesn’t become less inefficient just because you’ve written it in Go or something.

So, I needed to come up with something better. PHP has evolved a lot since then, and become quite a powerful language, and I’ve learned better strategies for handling large datasets.

So, my goal was the simple task of replacing the heavy and complex core of our application monolith with something more performant and well designed, and have it work in all the parts of the app that use those data (which is almost the whole app).

How do I break this down into parts?

I’m not going to detail the actual work I did for this; as I said above, this is proprietary software, so the parts I’d be allowed to tell you wouldn’t make for a very interesting story.

Suffice to say, we ended up breaking it into two steps, and it’s a strategy for dealing with large projects that we’ve come to employ a lot: the part you’re doing now, and the rest.

Kinda like how Elixir represents a list: it’s defined by the first element, then the rest of the list:

[head | tail] = [1, 2, 3]

To traverse the list, you just take the first element, the head, and just make the tail your new list, recursively until you run out of elements.

This is simple. It’s kinda obvious and kinda dumb. And that’s why I like it.

Step 1: draw some circles

Before I could replace the old data structure, I have to design the new one. This took a lot of conceptual work, research into how to handle very large datasets in PHP efficiently across our various use cases, and architecting and building the scaffolding for what would become the new system.

I built the prototype, got it working, and showed the CTO. It was (and is), if I may say so, an excellent, high-performance system. But it’s also isolated. It’s sitting there, in its corner of the codebase, not plugged into anything — everything still uses the old system.

The CTO said, this is brilliant. All you need to do now is draw the rest of the owl.

The silly meme at the top of the page has become something we refer to constantly when scoping out big projects. It’s supposed to make fun of unhelpful guides for breaking down complex work, but we’ve embraced it. It’s about looking at any task as the thing you need to do next, and the rest. It makes a project feel less daunting, because we can tell ourselves that’s only two things.

An artist doesn’t plan every barb on every feather before she even knows what pose to draw the owl in; she blocks the whole thing out with basic geometry first, and then just works on each detail as she gets to it.

I’m currently porting one of our features to use our new data structure, and I’m part way through a list of over 200 sub-features that need to be converted. My current plan is the next sub-feature on the list, and the rest.

And that’s only two things.